Why I Let a 12-Inch Robot Fly My Flight Simulator (And Why It Scared Me)

The “Toy” That Punched My Monitor

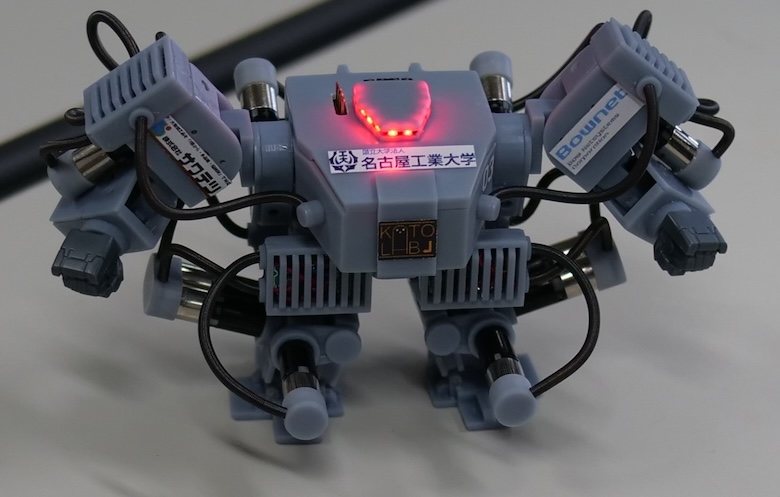

I spent last Tuesday night arguing with a piece of plastic the size of a toddler’s doll. It wasn’t a Furby. It was one of those new high-torque micro-humanoids that hit the hobbyist market late last year. You know the ones—they don’t just walk; they’re designed to operate things.

The marketing pitch is seductive. “Why automate the software when you can automate the user?”

So, naturally, I bought one. My goal was simple: get this little guy to fly a Cessna 172 in X-Plane using a physical yoke and throttle quadrant. No USB integration. No cheating. I wanted the robot to physically grab the controls with its tiny, silicone-tipped grippers and fly the plane like a miniature human pilot.

It didn’t go well at first. The robot, which I’ve named “Crash,” overcorrected on takeoff and literally punched my monitor. But after three hours of calibration and a lot of cursing, something clicked. It flew. It actually flew. And watching a toy-sized machine visually scan a cockpit dashboard and physically adjust a throttle lever gave me a weird feeling in the pit of my stomach. This isn’t just a toy anymore.

The Shift from Digital to Physical Interface

We’ve been looking at automation wrong for twenty years. We kept trying to make machines talk to machines digitally. We built APIs, we wrote drivers, we obsessed over protocols. But the world is full of “dumb” interfaces designed for human hands and eyes. Car steering wheels. Airplane cockpits. Industrial control panels with big red buttons.

The big news in the robotics community right now isn’t about smarter AI—it’s about these micro-pilots. The tech that started as a research gimmick in Korea a few years back has trickled down to the consumer level. We now have sub-$1,000 units capable of memorizing complex physical switch sequences.

I remember seeing early prototypes of this concept—robots like PIBOT—and thinking it was a parlor trick. Why put a robot in a pilot’s seat when you can just build a drone? But I missed the point. It’s not about building new planes for robots. It’s about robots that can operate the millions of legacy machines already in existence.

The unit I’m testing uses a localized vision model. It doesn’t “know” it’s flying. It knows that when the pixel array representing the artificial horizon tilts left, it needs to apply 4 Newtons of force to the right arm actuator. It’s terrifyingly effective.

Hardware Limitations: The Grip Problem

Let’s talk specs, because this is where the frustration sets in. If you’re thinking of picking up one of the new H-Series micro-bots, you need to know about the grip strength issue.

Human hands are soft, compliant, and incredibly strong. Robot hands—especially on a 40cm frame—are rigid and weak. My robot struggled to maintain a grip on the yoke during “turbulence” (me shaking the desk). The servos in the fingers just don’t have the torque density yet.

I had to wrap my flight yoke in grip tape just so Crash could hold on. It felt ridiculous. I’m modifying a $300 flight stick to accommodate an $800 robot, all to simulate a job that a $5 script could do better.

But then again, logic isn’t really the point of the hobby, is it?

The Latency Trap

Here’s something the spec sheets don’t tell you: visual processing latency is a killer. The robot has cameras in its head. It sees the screen, processes the image, decides on a move, and sends a signal to the servos.

That loop takes about 150 milliseconds on the current consumer hardware. In a flight sim, that’s fine. In a car? You’re dead. I tried letting it play a racing game and it careened into the wall on turn one every single time. Until we get faster onboard edge processing—maybe the NPU upgrades rumored for late 2026—these things are strictly for slow-moving tasks.

Why Are We Obsessed with Humanoid Form Factors?

I had a debate with a friend of mine, an engineer who works on industrial automation. He thinks humanoid robots are stupid. “Just build a box with wheels and a manipulator arm,” he says. “It’s more stable.”

He’s right, technically. But he’s also wrong.

![Small humanoid robot - CFC] Make a Creature with the Darwin Mini humanoid robot using a ...](https://aitoy-news.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/inline_e67c233b.jpg)

The reason these toy-sized pilots are selling out isn’t efficiency. It’s relatability. When I watch Crash struggle to reach the flap lever, I don’t see a machine malfunctioning. I see a little guy trying his best. I find myself rooting for him. “Come on, buddy, just a little more to the left.”

There’s also the universality argument. A humanoid form factor, even a tiny one, is the Swiss Army Knife of automation. The same robot that flies my simulator can, in theory, be picked up and placed in front of a toy piano, or a tiny typewriter. You don’t need three different robots. You just need one robot and three different software profiles.

The “Uncanny Valley” of Skill

Here is the weirdest part of my week with the robot. By Thursday, I had tuned the PID controllers enough that it could land the plane. Not smoothly—we bounced—but we didn’t crash.

Watching a plastic automaton perform a complex, high-skill human task like landing an aircraft triggers a specific kind of existential dread. It’s not the “Terminator” fear. It’s more subtle. It’s the realization that skills we consider “special” or “highly trained” are just math to these things.

It didn’t go to flight school. It didn’t sweat through check rides. I just downloaded a “Cessna_172_Landing.json” profile from a community forum, uploaded it via Bluetooth, and suddenly this toy was a better pilot than me.

What’s Coming Next?

If you’re looking at the roadmap for the rest of 2026, keep an eye on haptic feedback sensors for fingertips. Right now, these robots are numb. They rely entirely on vision to know if they’re holding something. Once they get pressure sensors in the fingertips (I’m hearing rumors about conductive silicone skins coming in Q3), the dexterity is going to skyrocket.

We’re also going to see a shift in battery tech. The current 20-minute run time on high-torque mode is pathetic. You can’t pilot a cross-country flight if you have to recharge over Kansas. I’ve ended up tethering mine to a USB-C power bank, which ruins the aesthetic but keeps the plane in the air.

Should You Buy One?

Look, if you want to automate tasks efficiently, write a script. If you want a reliable autopilot, use the one built into the software.

But if you want to feel like a mad scientist living in the future we were promised in 1980s sci-fi magazines? Yeah. Get one. Just maybe don’t let it near your expensive monitor until you’ve dialed down the arm velocity.

I’m keeping Crash. I even bought him a tiny aviator scarf. Don’t judge me.