Your Kid’s Coding Robot Is Probably a Snitch

It’s New Year’s Eve, and I’m Packet-Sniffing a Teddy Bear

I wish I was joking. It is December 31, 2025. Most people are prepping champagne or figuring out their resolutions. Me? I’m sitting here with Wireshark open, watching a plastic dog broadcast my home network details to a server in Shenzhen. Happy New Year.

If you bought a “programmable” or “smart” toy for a kid this holiday season, you might want to check what it’s actually doing. Because if the events of this year taught us anything, it’s that the toy industry still treats data privacy like a suggestion rather than a law.

I’m specifically thinking about the Justice Department’s smackdown of Apitor Technology earlier this year. Did you catch that? If you missed it between the endless AI hype cycles, here’s the gist: they got fined for violating the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA). Again. It’s always COPPA.

The government basically said, “Hey, stop collecting personal info from kids without asking their parents.” Groundbreaking, right? You’d think by 2025 we would have solved this. We haven’t.

The “Educational” Trap

Here’s how they get you. I fell for it myself a few years back.

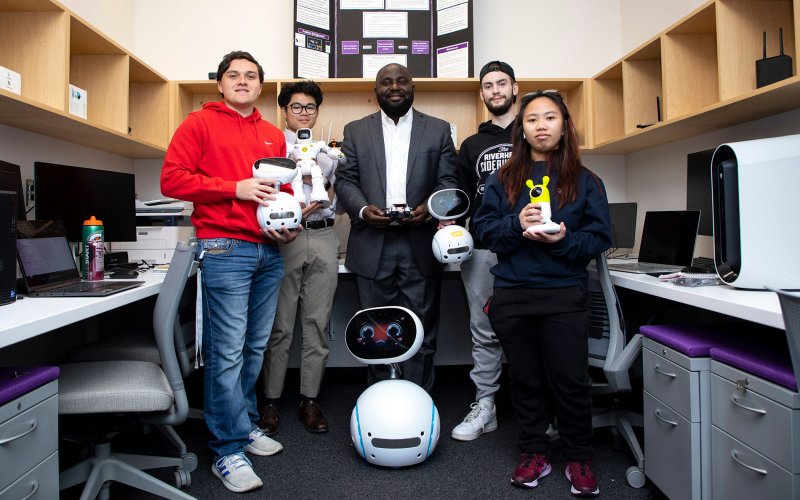

You see a kit. It promises to teach your seven-year-old Python or block-based coding. It looks like LEGO Technic but with brains. You think, “Great, I’m raising the next Wozniak.” You buy it.

Then comes Christmas morning. You open the box. There’s no manual, just a QR code. You scan it. It downloads an app. The app asks for microphone access. Then camera access. Then location. Then it wants you to create an account with a birthdate.

Why does a Bluetooth-controlled dump truck need my child’s exact birthdate and GPS coordinates?

The Apitor case was a perfect example of this laziness. They claimed the data collection was necessary for the “user experience.” Spoiler: it wasn’t. They were sucking up persistent identifiers—basically digital fingerprints—that let them track users across time and apps. For a toy.

It makes me furious because the hardware is usually cool. I love the sensors. I love the servo motors. But the software layer is a privacy nightmare wrapped in bright primary colors.

Under the Hood: Why This Keeps Happening

I’ve taken apart the APKs (Android package files) for a dozen of these toys. The pattern is always the same.

Developers use cheap, off-the-shelf SDKs (Software Development Kits) for Bluetooth and analytics. They don’t write their own networking code; they copy-paste it. And those default libraries are aggressive. They grab device IDs, Wi-Fi SSIDs, and sometimes even scan the local network for other devices.

In the Apitor case, the DOJ pointed out they weren’t even getting verifiable parental consent. That’s the “credit card check” or “signed form” step. It’s friction. Toy companies hate friction. Friction means the kid throws a tantrum because the robot isn’t moving yet, and the parent returns the box to Amazon.

So they skip it. They put a button that says “I am a Parent,” and assume that’s enough.

It’s not.

The Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) Excuse

Devs love to hide behind technical requirements. “We need Location permission to scan for Bluetooth Low Energy devices!”

Okay, technically, on older versions of Android, that was true. To find a BLE device, you needed location permissions because BLE beacons could theoretically be used to track location.

But it’s 2025. Modern mobile OS APIs have separated these permissions. If an app today is asking for “Precise Location” just to connect to a robot spider, they are either incompetent or lying. Usually both.

My “Paranoid Uncle” Vetting Process

Since I can’t stop my family from buying this stuff, I’ve developed a protocol. If you have these toys in your house right now—maybe under the tree that’s still up—here is what you do.

1. The Airplane Mode Test

Open the app. Connect to the toy. Then, cut the internet on the tablet or phone. Turn on Airplane Mode (but keep Bluetooth on).

Does the toy still work?

If yes, great. Keep it offline.

If the app screams “Connection Error” or refuses to load the coding interface without pinging a server, throw it in the trash. There is zero reason a local coding toy needs cloud connectivity to run a loop command.

2. The Permissions Audit

Go into your phone settings. Look at what the toy app has access to.

Camera? Revoke it.

Microphone? Revoke it.

Files and Media? Revoke it.

If the app crashes without these, it’s badly written. I’ve seen “coding” apps that refuse to launch if they can’t access the photo gallery. Why? Probably to save screenshots of code, but they take the lazy route and ask for everything.

3. Use a Burner Device

I don’t let these apps on my main phone. I have an old cracked iPad from 2020 that I use specifically for “unsafe” toys. It has no email accounts logged in, no contacts, no photos. It’s a ghost ship. If Apitor or anyone else wants to scrape data from that thing, they’re going to get a whole lot of nothing.

Looking Ahead to 2026

The fine against Apitor was significant ($100,000+ civil penalty, though often suspended based on inability to pay), but let’s be real—it’s a rounding error for the industry.

However, the compliance requirements were the interesting part. They were forced to delete the data. All of it.

I suspect by mid-2026, we’re going to see a shift. Not because companies developed a conscience, but because the liability is getting too high. We might finally see “Local-Only” become a marketing feature. Imagine a box that proudly says: “No Account Required. No Cloud. Just Code.”

I’d buy that in a heartbeat.

Until then, assume every robot, smart bear, and connected drone is a little spy. It’s not paranoia if the Department of Justice just sued them for doing exactly that.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I need to figure out why this robot dog is trying to ping a server in Frankfurt.