Stop Buying $1,000 Lab Mixers. Use Lego.

I was staring at a quote for a gradient mixer last Tuesday. The price tag? $1,250. For a machine that essentially just tilts a tube back and forth at a set speed. It’s insulting. Honestly, the markup on “scientific grade” equipment has always been a racket, but seeing four figures for a glorified teeter-totter broke something inside me.

And I didn’t buy it.

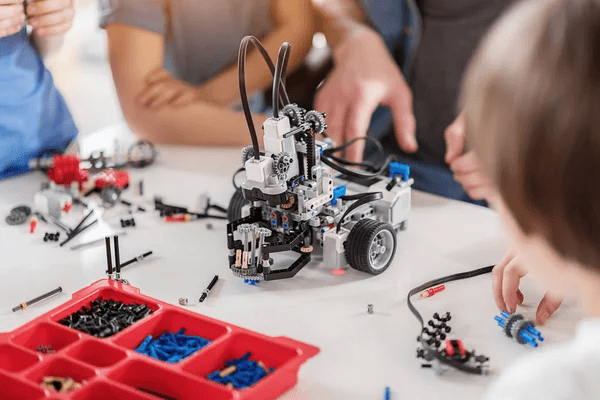

Instead, I dug out the dusty Lego SPIKE Prime kit I bought back in 2021—ostensibly for my nephew, but let’s be real—and decided to build the thing myself. If researchers could figure out how to purify DNA with these plastic bricks a few years ago, I could definitely build a simple mixer.

The “Toy” That Runs My Lab Bench

It sounds ridiculous until you look at the specs. The motors in modern consumer robotics kits are surprisingly capable servos with built-in rotation sensors. We aren’t talking about the simple DC motors from the 90s that just spun until the battery died. These things have position feedback accurate to within one degree, as documented in the official Lego Mindstorms documentation.

I set up a simple rig. Two medium motors, a Technic frame, and a custom 3D-printed holder for the Falcon tubes (because Lego doesn’t make a piece that fits a 50ml conical tube perfectly, obviously).

The coding part was where it got interesting. I flashed the hub with the latest MicroPython firmware (v1.22.1 as of January) because the default block-based coding environment is a nightmare for anything requiring precise timing, as outlined in the MicroPython documentation.

Here’s the thing about the Python API on these hubs: it’s robust. I wrote a script to oscillate the platform between -20 and +20 degrees at variable speeds.

The code looked something like this:

from hub import port, motion_sensor

import runloop

import motor

async def mix_cycle():

# Run for 5 minutes at speed 30

await motor.run_for_degrees(port.A, 7200, 30)

Simple. And it cost me effectively zero dollars since I already had the parts. If you had to buy it new today, a comparable kit is maybe $400. That’s still a third of the price of the “professional” equipment.

Where It Actually Breaks (The Real-World Test)

Well, that’s not entirely accurate — it wasn’t perfect.

The first run was a disaster. I underestimated the torque required to tilt a full rack of buffer solution. The plastic gears inside the medium motor started skipping—that horrible click-click-click sound that haunts anyone who’s ever built a complex Technic set.

I had to gear it down. 3:1 ratio. This fixed the torque issue but introduced backlash.

This is the trade-off nobody talks about with DIY lab gear. Precision vs. slop. When I measured the tilt angle with an external inclinometer, I was getting a variance of about ±2.5 degrees due to the play in the plastic gears. For mixing a buffer? Who cares. It works fine. But if you’re trying to build a gradient mixer where the angle determines the flow rate and concentration gradient? That slop matters.

I ended up using rubber bands to tension the gears and remove the slack. It looks janky as hell—literally blue rubber bands holding a scientific instrument together—but it dropped the variance to under 0.5 degrees.

Why This Matters in 2026

We are seeing a weird bifurcation in hardware right now. On one side, you have proprietary, black-box lab equipment that requires a subscription or a service technician just to calibrate. But on the other, you have open-source hardware and, increasingly, consumer toys being repurposed for serious work.

I’m seeing this more often. Just last month, a colleague showed me a centrifuge they built using a drone motor and a 3D-printed rotor. It spins at 12,000 RPM. Is it safe? Probably not. Does it work for quick spin-downs? Absolutely.

The Lego approach has a specific advantage over the drone motor method, though: reproducibility. If I share my Python script and the Lego build instructions (an LDR file), anyone in a lab in Brazil, Kenya, or a high school in Ohio can build the exact same machine. They don’t need to source a specific brushless motor from AliExpress that might go out of stock next week. They just need the kit.

The “Gotcha” with Firmware Updates

But there is one massive headache I ran into, and if you try this, you need to know about it. Automatic firmware updates.

I had my rig running perfectly. Then, I connected the hub to the app on my iPad to check the battery level. The app forced a firmware update.

The new firmware changed how the motor_pair class handled acceleration ramps. Suddenly, my gentle mixing action became a violent shake that nearly launched a tube across the room.

Lesson learned: If you use consumer hardware for production work, air-gap it. Never connect it to the official app once it’s working. Treat it like a legacy server.

The Verdict

Is my Lego mixer as good as the $1,250 one? No. It’s louder, it looks unprofessional, and I have to replace the rubber bands every two weeks because they dry out.

But it purified the samples just fine. The yield was identical to the control group processed on the expensive machine.

We’re at a point where “good enough” hardware is becoming accessible to everyone. You don’t need a grant to do good science anymore; sometimes you just need to raid the toy box. Just maybe don’t tell the safety officer about the centrifuge.